Sodium. Potassium. Glucose. Lactate. Engineers at the University of California, Berkeley are focusing on measuring these components of sweat in an attempt to open an additional window into an individual’s health and well-being. A new device is able to calibrate the data based on skin temperature and transmit the information wirelessly in real time to a smartphone. The results of a new study of the wearable technology have been published in the journal Nature.

“Human sweat contains physiologically rich information, thus making it an attractive body fluid for noninvasive wearable sensors,” says Ali Javey, a UC Berkeley professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences, and senior author of the study. “However, sweat is complex and it is necessary to measure multiple targets to extract meaningful information about your state of health. In this regard, we have developed a fully integrated system that simultaneously and selectively measures multiple sweat analytes.”

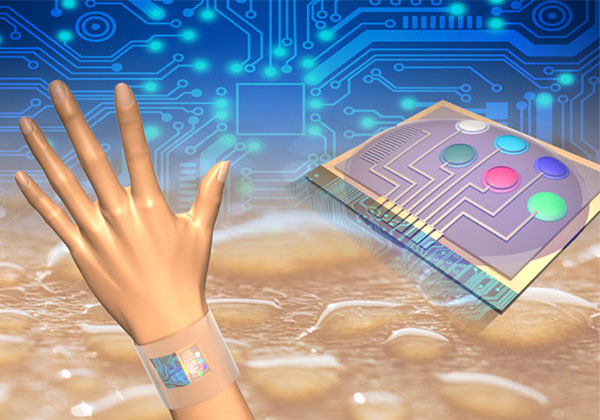

Javey and his research team developed a prototype that comprises a flexible printed circuit board holding five sensors. The device was attached to “smart” wristbands and headbands and used on 26 volunteers who performed various exercises of differing levels of intensity, and for varying lengths of time, both indoors and outdoors. The data collected was then processed and wirelessly transmitted using Bluetooth to a smartphone.

The researchers are not alone in their quest to squeeze every drop of data possible out of human perspiration. A “sweat test,” which measures the amount of chloride in an individual’s sweat, is considered the “gold standard” for diagnosing cystic fibrosis, a genetic disease that causes chronic lung infections and respiratory issues. In addition, a team at the University of Cincinnati’s Novel Devices Lab, working with scientists from the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory, has developed a patch that stimulates skin and gathers data from sweat. The research began five years ago with the intent to find a convenient way to monitor an airman’s response to disease, medication, diet, injury, stress, and other physical changes during military training and missions.

Javey concedes that sweat sensors will never be as accurate as blood tests. “Our bodies closely control the molecular composition of our blood, but the content of our sweat is more variable and is sometimes influenced by microbes on our skin — so the medical relevance of the information that sweat provides will need to be rigorously tested,” he explains. “However, sweat does have an advantage: taking blood samples with a needle is not a practical means of assessing health on a minute-by-minute basis.”

For more detail: Wearable sensors analyze your sweat