The other day Linda from Purchasing came to me with a problem: Lou from Operations needed to source a replacement for a shorted diode on a switching power supply. The darned thing was marked with a strange part number that no amount of Googling could decipher.

Fortunately there was a second identical unit in for repair, and Lou was able to provide me with a good diode of the same type. Now all I had to do was figure out what it was. A standard rectifier diode? A zener? Schottky? Reverse voltage breakdown rating? Junction capacitance? Recovery time?

From the DO-41 package size it was easy to deduce that the rating was a watt. It was also easy to inject various currents and measure the forward voltage drop to determine that it was not a Schottky diode. Hooking up a few power supplies in series and gradually increasing the reverse voltage (with adequate series current limiting resistance in case a zener threshold was reached) proved it was not a zener diode – at least not below 200 volts.

The required PIV rating could be resolved by initially substituting a test diode with a high voltage rating, and scoping later.

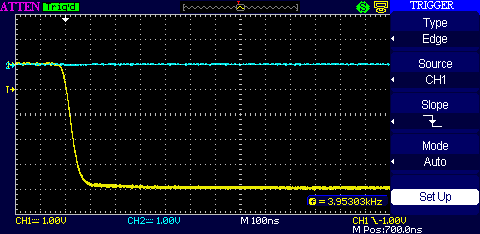

This left only the unknown junction capacitance, Cj, and reverse recovery time, Trr. This is the time that a diode remains conducting when suddenly switched from forward to reverse biased. I had to figure out a way to measure these parameters. Not with exotic equipment; just enough to get in the ballpark – in other words, a function generator with a falltime of 40ns, and a 100MHz scope, which was all I had to work with.

For more detail: Easily measure diode capacitance and reverse recovery